Introduction to Java programming. This tutorial explains the installation and usage of the Java programming language. It also contains examples for standard programming tasks.

1. Introduction to Java

1.1. A small history of Java

Java is a programming language created by James Gosling from Sun Microsystems (Sun) in 1991. Java allows you to write a program and run it on multiple operating systems. The first publicly available version of Java (Java 1.0) was released in 1995. Sun Microsystems was acquired by the Oracle Corporation in 2010. Oracle now has the stewardship for Java. In 2006 Sun started to make Java available under the GNU General Public License (GPL). Oracle continues this project called OpenJDK.

Currently every 3 months a new version of Java is released. Certain versions are supported for 2 years and are called long-term maintenance (LTM), regular versions only for 6 months. The current LTM version of Java is Java 21.

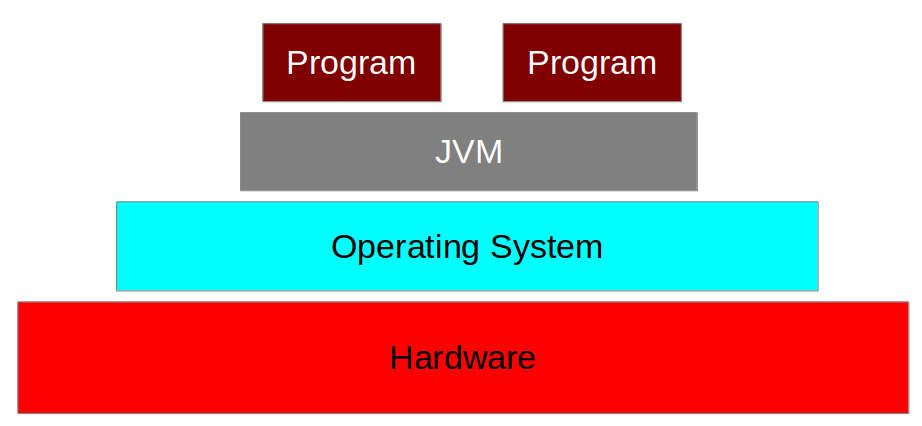

Java is defined by a specification and consists of a programming language, a compiler, core libraries and a runtime (Java Virtual Machine).

The Java language was designed with the following properties:

-

Platform independent: Java programs use the Java Virtual Machine as abstraction and do not access the operating system directly. This makes Java programs highly portable. A Java program (which is standard-compliant and follows certain rules) can run unmodified on all supported platforms, e.g., Windows or Linux.

-

Object-oriented programming language: Except the primitive data types, all elements in Java are objects.

-

Strongly-typed programming language: Java is strongly-typed, e.g., the types of the used variables must be predefined and conversion to other objects is relatively strict, e.g., must be done in most cases by the programmer.

-

Interpreted and compiled language: Java source code is transferred into the bytecode format which does not depend on the target platform. These bytecode instructions will be interpreted by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). The JVM contains a so-called Hotspot-Compiler which translates performance critical bytecode instructions into native code instructions.

-

Automatic memory management: Java manages the memory allocation and de-allocation for creating new objects. The program does not have direct access to the memory. The so-called garbage collector automatically deletes objects to which no active pointer exists.

Java is case-sensitive, e.g., variables called myValue and myvalue are treated as different variables.

1.2. Hello world Java program

// a small Java program

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}1.3. Java Virtual Machine

The Java Virtual Machine (JVM) is a software implementation of a computer that executes programs like a real machine.

The Java Virtual Machine is written specifically for a specific operating system, e.g., for Linux a special implementation is required as well as for Windows.

Java programs are compiled by the Java compiler into bytecode. The Java Virtual Machine interprets this bytecode and executes the Java program.

1.4. Development Process with Java

Java source files are written as plain text documents. The programmer uses a text editor or an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) for creating these text documents. An IDE supports the programmer in the task of writing code, e.g., it provides auto-formatting of the source code, highlighting of the important keywords, etc. Typical Java IDEs are Visual Studio Code or the Eclipse IDE.

The Java runtime executes bytecode instructions.

Therefore the text files must be converted from text to bytecode.

These instructions are stored in .class files and can be executed by the Java Virtual Machine.

This can be done via the Java compiler(javac), either by the programmer by calling the Java compiler directly or by the IDE.

1.5. Garbage collector

The Java runtime automatically frees the memory which is not referred to by other objects. The Java garbage collector checks all object references and finds the objects that can be automatically released.

While the garbage collector relieves the programmer from the need to explicitly manage memory, the programmer still needs to ensure that he does not keep unneeded object references, otherwise the garbage collector cannot release the associated memory. Keeping unneeded object references is typically called memory leaks.

1.6. Classpath

The classpath defines where the Java compiler and Java runtime look for .class files to load.

These instructions can be used in the Java program.

For example, if you want to use an external Java library you have to add this library to your classpath to use it in your program.

2. Installing Java

If your installation requires installing the Java runtime, ensure that you install the latest Java long-term release. At the time of this writing, this is Java 21. Later versions of Java are suitable to use as well.

You can test whether the JRE is correctly installed by using the Windows console. To open a console on Windows, press Win+R, type cmd, and press Enter. Next, type the following command:

java -versionIf the JRE is correctly installed, this command prints information about your Java installation. If you see that you have the desired JRE version installed, no additional step is necessary.

If the command line indicates that the program could not be found, you need to install Java.

You can get a Java runtime from https://adoptium.net/. It contains instructions on how to install Java for all supported platforms. For the Windows and Mac platform, you also find native installer software.

If you have problems installing Java on your system, search online using a query like "How to install Java runtime on [YOUR OS]."

Replace YOUR OS with your operating system, e.g., Windows, Ubuntu, macOS, etc.

This should result in helpful links.

3. Exercise: Write, compile and run a Java program

3.1. Write source code

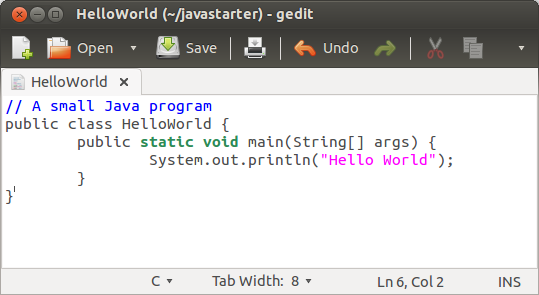

The following Java program is developed under Linux using a text editor and the command line. The process on other operating systems should be similar, but is not covered in this description.

Select or create a new directory which will be used for your Java development.

In this description the path /home/vogella/javastarter is used.

On Microsoft Windows you might want to use c:\temp\javastarter.

This path is called javadir in the following description.

Open a text editor which supports plain text, e.g., gedit under Linux or Notepad under Windows and write the following source code.

// a small Java program

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}| Do not use a rich editor like Microsoft Word or LibreOffice for writing Java code. If in doubt, google for "Plain text editor for [your_OS]". |

Save the source code in your javadir directory with the HelloWorld.java filename.

The name of a Java source file must always equal the class name (within the source code) and end with the .java extension.

In this example, the filename must be HelloWorld.java, because the class is called HelloWorld.

3.2. Compile and run your Java program

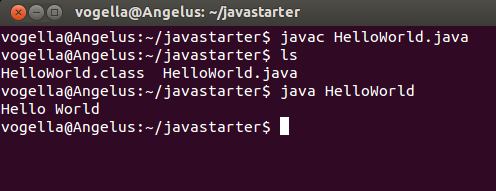

Open a shell for command line access.

| If you do not know how to do this, google for "How to open a shell under [your_OS]". |

Switch to the javadir directory with the command cd javadir, for example, in the above example via the cd \home\vogella\javastarter command.

Use the ls command (dir under Microsoft Windows) to verify that the source file is in the directory.

Compile your Java source file into a class file with the following command.

javac HelloWorld.javaAfterwards, list again the content of the directory with the ls or dir command.

The directory contains now a file HelloWorld.class.

If you see this file, you have successfully compiled your first Java source code into bytecode.

By default, the compiler puts each class file in the same directory as its source file. You can specify a separate destination directory with the -d compiler flag.

|

You can now start your compiled Java program. Ensure that you are still in the javadir directory and enter the following command to start your Java program.

java HelloWorldThe system should write "Hello World" on the command line.

3.3. Using the classpath

You can use the classpath to run the program from another place in your directory.

Switch to the command line, e.g., under cmd.

Switch to any directory you want. Type:

java HelloWorldIf you are not in the directory in which the compiled class is stored, then the system will show an error message: Exception in thread "main" java.lang.NoClassDefFoundError: test/TestClass

To use the class, type the following command. Replace "mydirectory" with the directory that contains the test directory. You should again see the "HelloWorld" output.

java -classpath "mydirectory" HelloWorld4. Base Java language structure

4.1. Class

A class is a template that describes the data and behavior associated with an instance of that class.

A class is defined by the class keyword and must start with a capital letter. The body of a class is surrounded by {}.

package test;

class MyClass {

}The data associated with a class is stored in variables; the behavior associated to a class or object is implemented with methods.

A class is contained in a text file with the same name as the class plus the .java extension.

It is also possible to define inner classes, these are classes defined within another class, in this case you do not need a separate file for this class.

4.2. Object

An object is an instance of a class.

The object is the real element which has data and can perform actions. Each object is created based on the class definition. The class can be seen as the blueprint of an object, i.e., it describes how an object is created.

4.3. Package

Java groups classes into functional packages.

Packages are typically used to group

classes into logical

units.

For

example, all graphical views of an application might

be placed in

the

same package called

com.vogella.webapplication.views.

It is

common practice to use the

reverse

domain name of the company as

top

level package. For example,

the

company might own

the domain,

vogella.com and in this example

the

Java

packages of this company starts

with

com.vogella.

Other main reason for the usage of packages is to avoid name collisions of classes. A name collision occurs if two programmers give the same fully qualified name to a class. The fully qualified name of a class in Java consists of the package name followed by a dot (.) and the class name.

Without packages, a programmer

may

create a Java class

called

Test.

Another programmer may create

a class with the same name. With

the

usage of packages you can

tell the system which class

to call.

For

example, if the first programmer puts

the

Test

class into package

report

and the second programmer

puts his class into package

xmlreader

you can distinguish between these classes by using the

fully qualified name,

e.g,

xmlreader.Test

or

report.Test.

4.4. Inheritance

A class can be derived from another class. In this case this class is called a subclass. Another common phrase is that a class extends another class.

The class from which the subclass is derived is called a superclass.

Inheritance allows a class to inherit the behavior and data definitions of another class.

The following codes demonstrates how a class can extend another class. In Java a class can only extend a maximum of one class.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

class MyBaseClass {

public void hello() {

System.out.println("Hello from MyBaseClass");

}

}package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

class MyExtensionClass extends MyBaseClass {

}4.5. Object as superclass

Every object in Java implicitly extends the

Object

class. The class defines the following methods for every Java

object:

-

equals(o1)allows checking if the current object is equal to o1 -

getClass()returns the class of the object -

hashCode()returns an identifier of the current object -

toString()gives a string representation of the current object

4.6. Exception handling in Java

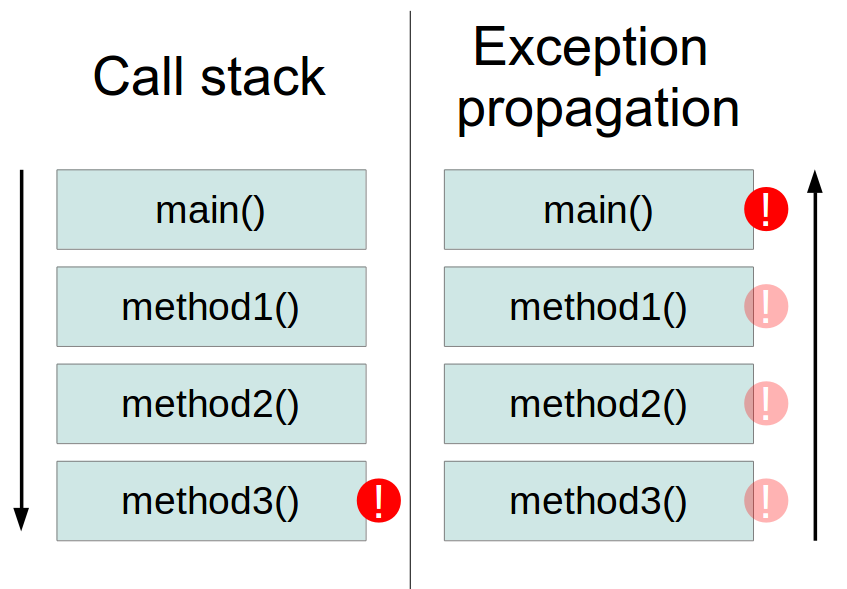

In Java an exception is an event to indicate an error during the runtime of an application. So this disrupts the usual flow of the application’s instructions.

In general, exceptions are thrown up in the call hierarchy until they are caught.

4.7. Checked Exceptions

Checked Exceptions are explicitly thrown by methods, which might cause the exception or re-thrown by methods in case a thrown Exception is not caught.

So when calling methods, which throw checked Exceptions the Exceptions have either to be caught or to be re-thrown.

public void fileNotFoundExceptionIsCaughtInside() {

try {

createFileReader();

} catch (FileNotFoundException e) {

logger.error(e.getMessage(), e);

}

}

public void fileNotFoundExceptionIsReThrown() throws FileNotFoundException {

createFileReader();

}

public void createFileReader() throws FileNotFoundException {

File file = new File("/home/Documents/JavaTraining.txt");

// creating a new FileReader can cause a FileNotFoundException

new FileReader(file);

}Checked Exceptions are used when an error can be predicted under certain circumstances, e.g., a file which cannot be found.

4.8. Runtime Exceptions

Runtime Exceptions are Exceptions that are not explicitly mentioned in the method signature and therefore also do not have to be caught explicitly.

The most famous runtime exception is the NullPointerException, which

occurs during runtime, when a method is invoked

on an object, which

actually is

null.

public void causeANullPointerException() {

String thisStringIsNull = getMessage(false);

// because the thisStringIsNull object is null

// this will cause a NullPointerException

thisStringIsNull.toLowerCase();

}

public String getMessage(boolean messageIsAvailable) {

if(messageIsAvailable) {

return message;

}

return null;

}5. Java interfaces

5.1. What is an interface in Java?

An interface is a type similar to a class and is defined via the interface keyword.

Interfaces are used to define common behavior of implementing classes.

If two classes implement the same interface, other code that works on the interface level can use objects of both classes.

Like a class an interface defines methods. Classes can implement one or several interfaces. A class that implements an interface must provide an implementation for all abstract methods defined in the interface.

5.2. Abstract, default and static methods in Interfaces

An interface can have abstract methods and _default_methods.

A default method is defined via the default keyword at the beginning of the method signature.

All other methods defined in an interfaces are public and abstract; explicit declaration of these modifiers is optional.

Interfaces can have constants that are always implicitly public, static and final.

The following code shows an example implementation of an interface.

package testing;

public interface MyInterface {

// constant definition

String URL = "https://www.vogella.com/";

// public abstract methods

void test();

void write(String s);

// default method

default String reserveString(String s){

return new StringBuilder(s).reverse().toString();

}

}5.3. Implementing Interfaces

A class can implement an interface.

In this case it must provide specific implementations of the abstract interface methods.

If you implement a method defined by an interface, you can use @Override annotation.

This indicates to the Java compiler that you actually want to implement a method defined by this interface.

This way the compiler can give you an error if you mis-typed the name of the method or in the number of arguments.

The following class implements the MyInterface interface, it must therefore implement the abstract method and can use the default methods.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public class MyClassImpl implements MyInterface {

@Override

public void test() {

}

@Override

public void write(String s) {

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

MyClassImpl impl = new MyClassImpl();

System.out.println(impl.reserveString("Lars Vogel"));

}

}5.4. Evolving interfaces with default methods

Java supports default methods in interfaces, you can extend an interface without breaking clients by supplying a default implementation with it. Adding such a default method is a source and binary compatible change.

A class can always override a default method to supply a better behavior.

5.5. Multiple inheritance of methods

If a class implements two interfaces and if these interfaces provide the same default method, Java resolves the correct method for the class by the following rules:

-

Superclass wins always against the superinterface - If a class can inherit a method from a superclass and a superinterface, the class inherits the superclass method. This is true for concrete and abstract superclass methods. This rule implies that default methods are not used if this method is also declared in the superclass chain.

-

Subtypes win over Supertypes - If a class can inherit a method from two interfaces, and one is a subtype of the other, the class inherits the method from the subtype

-

In all other cases the class needs to implement the default method

The following listing demonstrates listing number 3.

public interface A {

default void m() {}

}

public interface B {

default void m() {}

}

public class C implements A, B {

@Override

public void m() {}

}In your implementation you can also call the super method you prefer.

public class C implements A, B {

@Override

public void m() {A.super.m();}

}5.6. Functional interfaces

All interfaces that have only one method are called functional interfaces. Functional interfaces have the advantage that they can be used together with lambda expressions. See What are lambdas? to learn more about lambdas, e.g., the type of lambdas is a functional interface.

The Java compiler automatically identifies functional interfaces.

The only requirement is that they have only one abstract method.

However, is possible to capture the design intent with a @FunctionalInterface

annotation.

Several default Java interfaces are functional interfaces:

-

java.lang.Runnable -

java.util.concurrent.Callable -

java.io.FileFilter -

java.util.Comparator -

java.beans.PropertyChangeListener

Java also contains the java.util.function package that contains functional interfaces that are frequently used such as:

-

Predicate<T> - a boolean-valued property of an object

-

Consumer<T> - an action to be performed on an object

-

Function<T, R> - a function transforming a T to a R

-

Supplier<T> - provides an instance of T (such as a factory)

-

UnaryOperator<T> - a function from T to T

-

BinaryOperator<T> - a function from (T, T) to T

6. Annotations in Java

6.1. Annotations in Java

Annotations provide data about a class that is not part of the programming logic itself. They have no direct effect on the code they annotate. Other components can use this information.

Annotations can

be preserved at runtime (RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

or are only available at development time (RetentionPolicy.SOURCE).

6.2. Override methods and the @Override annotation

If a class extends another class, it inherits the methods from its superclass. If it wants to change these methods, it can override these methods, i.e., redeclare the methods. This is necessary for an abstract method unless the class itself is defined as abstract.

The

@Override

annotation can be added to such a method.

It is used by the Java compiler to check if the annotated method overrides a method of an interface or the extended class.

To override a method, you use the same method signature in the source code of the subclass.

To indicate to the reader of the source code and the Java compiler

that you have the intention to override a method,

you can use the

@Override

annotation.

The following code demonstrates how you can override a method from a superclass.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

class MyBaseClass {

public void hello() {

System.out.println("Hello from MyBaseClass");

}

}package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

class MyExtensionClass2 extends MyBaseClass {

@Override

public void hello() {

System.out.println("Hello from MyExtensionClass2");

}

}It is a good practice to always use the

@Override

annotation. This way the Java compiler validates if you did override

all methods as intended and prevents errors.

6.3. The @Deprecated annotations

The @Deprecated annotation can be used on a field, method, constructor or class and indicates that this element is outdated and should not be used anymore.

Adding @Deprecated to the class does not deprecate automatically all its fields and methods.

6.4. Type annotations

Java supports that annotations can be placed on any type. The following gives several examples assuming the annotations exists.

@NonNull String name;

List<@NonNull String> names;

class UnmodifiableList<T> implements @Readonly List<@Readonly T> {...}

email = (@Email String) input;

new @Information MyObject();

void doSomething() throws @ImportantForMe MyException { ... }7. Variables and methods

7.1. Variable

Variables allow the Java program to store values during the runtime of the program.

A variable can either be a: * primitive variable * reference variable

A primitive variable contains the value.

A reference variable contains a reference (pointer) to the object.

Hence, if you compare two reference variables, you compare if both point to the same object.

To identify if objects contain the same data, use the object1.equals(object2) method call.

7.2. Instance variable

An instance variable is associated with an instance of the class (also called object). Access works over these objects.

Instance variables can have any access control and can be marked final or transient.

Instance variables marked as final cannot be changed after a value has been assigned to them.

7.3. Local variable

Local (stack) variable declarations cannot have access modifiers. Local variables do not get default values, so they must be initialized before they can be used.

final is the only modifier available to local variables. This modifier defines that the variable cannot be changed after the first assignment.

7.4. Methods

A method is a block of code with parameters and a return value. It can be called on the object.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public class MyMethodExample {

void tester(String s) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}Methods can be declared with var-args. In this case the method declares a parameter that accepts everything from zero to many arguments (syntax: type … name;) A method can only have one var-args parameter and this must be the last parameter in the method.

Overwrite of a superclass method: A method must be of the exact same return parameter and the same arguments.

Overload methods: An overloaded method is a method with the same name, but different arguments. The return type cannot be used to overload a method.

7.5. Main method

A public static method with the following signature can be used

to

start a Java application. Such a method is typically called

main

method.

public static void main(String[] args) {

}7.6. Constructor

A class contains constructors that are invoked by the Java runtime to create objects based on the class definition.

Constructor declarations look like method declarations except that they use the name of the class and have no return type.

A class can have several constructors with different parameters.

In the following example the constructor of the class expects a parameter.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public class MyConstructorExample2 {

String s;

public MyConstructorExample2(String s) {

this.s = s;

}

}Each class must define at least one constructor. If no explicit constructor is defined in the Java source file, the compiler implicitly adds a constructor. If the class is sub-classed, then the constructor of the super class is always called implicitly in this case.

In the following example the definition of the constructor without parameters (also known as the empty constructor) is unnecessary. If not specified, the compiler would create one.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public class MyConstructorExample {

// unnecessary: would be created by the compiler if left out

public MyConstructorExample() {

}

}The naming convention for creating a constructor is the following:

classname (Parameter p1, …) { }.

Every object is created based on a constructor. This constructor method is the first statement called before anything else can be done with the object.

8. Modifiers

8.1. Access modifiers

There are three access modifiers keywords available in Java: * public * protected * private

There are four access levels: public, protected, default and private.

They define how the corresponding element is visible to other components.

If something is declared public, e.g., classes or methods can be freely created or called by other Java objects. If something is declared private, e.g., a method, it can only be accessed within the class in which it is declared.

The access levels protected and default are similar. A protected class can be accessed from the package and sub-classes outside the package, while a default class can get accessed only via the same package.

The following table describes the visibility:

| Modifier | Class | Package | Subclass | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|

public |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

protected |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

no modifier |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

private |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

8.2. Other modifiers

final methods: cannot be overwritten in a subclass abstract method: no method body

synchronized method: thread safe, can be final and have any access control

native methods: platform-dependent code, apply only to methods

strictfp: class or method

9. Import statements

9.1. Usage of import statements

You have to access a Java class always via its full-qualified name, i.e., the package name plus a . followed by the class name.

You can add import statements into your class file.

These allow you to use the related classes in your code without the package qualifier.

9.2. Static imports

Static import allows public static members (fields and methods) of another class to be used in Java code without a class reference.

The feature provides a typesafe mechanism to include constants in code. It also improves code readability and allows Java API designers to write a concise API.

10. More Java language constructs

10.1. Class methods and class variables

Class methods and class variables are associated with the class and not an instance of the class, i.e., objects. To refer to these elements, you can use the class name and a dot (".") followed by the class method or class variable name.

Class methods and class variables are declared with the

static

keyword. Class methods are also called

static methods

and class variables are also called

static variables

or

static fields.

An example of the usage of a static field is

println

of the following statement:

System.out.println("Hello World").

Hereby

out

is a static field, an object of type

PrintStream

and you call the

println()

method on this object.

If you define a static variable, the Java runtime environment associates one class variable for a class no matter how many instances (objects) exist. The static variable can therefore be seen as a global variable.

The following code demonstrates the usage of

static

fields.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public class MyStaticExample {

static String PLACEHOLDER = "TEST";

static void test() {

System.out.println("Hello");

}

}package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public class Tester {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(MyStaticExample.PLACEHOLDER);

MyStaticExample.test();

}

}If a variable should be defined as constant, you declare it with the

static

and the

final

keyword.

The static method runs without any instance of the class, it cannot directly access non-static variables or methods.

10.2. Abstract class and methods

A class and method can be declared as

abstract.

An

abstract

class cannot be directly instantiated.

If a class has at least one method, which only contains the declaration

of

the method, but not the implementation, then this class is

abstract

and

cannot be instantiated. Sub-classes need then to define the

methods

except if they are also declared as abstract.

If a class contains an abstract method, it also needs to get defined with the abstract keyword.

The following example shows an abstract class.

package com.vogella.javaintro.base;

public abstract class MyAbstractClass {

abstract double returnDouble();

}11. Cheat Sheets

During your Java development time, you will be asked to do certain things, like creating a local variable. The following can be used as a reference for such tasks, so that you know what you have to do.

11.1. Working with classes

While programming Java you have to create several classes, methods, instance variables. The following uses the package test.

What to do |

How to do it |

Create a new class called MyNewClass. |

|

Create a new attribute (instance variable) called var1 of type |

|

Create a Constructor for your

|

|

Create a new method called doSomeThing in your class which does not return a value and has no parameters. |

|

Create a new method called

doSomeThing2

in your class which does

not

return a value and has two parameters,

an |

|

Create a new method called

doSomeThing3

in your class which

returns an |

|

Create a class called MyOtherClass with two instance

variables.

One will store a |

|

11.2. Working with local variable

A local variable must always be declared in a method.

| What to do | How to do it |

|---|---|

Declare a (local) variable of type |

|

Declare a (local) variable of type |

|

Declare a (local) variable of type |

|

Declare a (local) variable of type |

|

Declare an array of type |

|

Declare an array of type |

|

Assign 5 to the |

|

Assign the existing variable |

|

Declare an |

|

Create a new |

|

Declare an |

|

12. Integrated Development Environment

The previous chapter explained how to create and compile a Java program on the command line. A Java Integrated Development Environment (IDE) provides lots of ease of use functionality for creating Java programs. There are other powerful IDEs available, for example, the Eclipse IDE.

For an introduction on how to use the Eclipse IDE please see Eclipse IDE Tutorial.

The remaining description uses the phrase: "Create a Java project called…". This refers to creating a Java project in Eclipse. If you are using a different IDE, please follow the required steps in that IDE.

13. Exercises - Creating Java objects and methods

13.1. Create a Person class and instantiate it

Create a new Java project called com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1 and a package with the same name.

Create a class called Person.

Add three instance variables to it, one for storing the first name of the person, one for storing the last name and one for storing the age of the Person.

Use the constructor of the Person object to set the values to some default value.

Add a toString method as described by the following coding and solve the TODO.

This method is used to convert the object to a String representation.

@Override

public String toString() {

// TODO replace "" with the following:

// firstName + " " + lastName

return "";

}Create a new class called Main with a public static void main(String[] args).

In this method create an instance of the Person class.

13.2. Use constructor

Add a constructor to your Person class which takes first name, last name and age as parameter.

Assign the values to your instance variables.

In your main method create at least one object of type Person and use System.out.println() with the object as parameter.

13.3. Define getter and setter methods

Define methods that allow you to read the values of the instance variables and to set them. These methods are called setter and getter.

Getters should start with get followed by the variable name whereby the first letter of the variable is capitalized.

Setter should start with set followed by the variable name whereby the first letter of the variable is capitalized.

For example, the variable called firstName would have the getFirstName() getter method and the setFirstName(String s) setter method.

Change your main method so that you create one Person object and use the setter method to change the last name.

13.4. Create an Address object

Create a new object called Address.

The Address should allow you to store the address of a person.

Add a new instance variable of this type in the Person object.

Also, create a getter and setter for the Address object in the Person object.

14. Solution - Creating Java objects and methods

14.1. Create a Person class and instantiate it

The following is the expected result after the creation of a Person class and it gets instantiated.

package exercises.exercise04;

class Person {

String firstname = "Jim";

String lastname = "Knopf";

int age = 12;

@Override

public String toString() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

}package exercises.exercise04;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Person person = new Person();

// this calls the toString method on the pers object

System.out.println(pers);

}

}14.2. Use constructor

The following is the expected result after the usage of the constructor.

package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

class Person {

String firstName;

String lastName;

int age;

public Person(String a, String b, int value) {

firstName = a;

lastName = b;

age=value;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

}package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Person p1 = new Person("Jim", "Knopf" , 12 );

System.out.println(p1);

// reuse the same variable and assign a new object to it

Person p2 = new Person("Henry", "Ford", 104);

System.out.println(p2);

}

}14.3. Define getter and setter methods

The following is the expected result after the definition of getter and setter methods.

package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

class Person {

String firstName;

String lastName;

int age;

public Person(String a, String b, int value) {

firstName = a;

lastName = b;

age = value;

}

public String getFirstName() {

return firstName;

}

public void setFirstName(String firstName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public String getLastName() {

return lastName;

}

public void setLastName(String lastName) {

this.lastName = lastName;

}

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

public void setAge(int age) {

this.age = age;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

}package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Person person = new Person("Jim", "Knopf", 21);

Person p2 = new Person("Jill", "Sanders", 20);

// Jill gets married to Jim

// and takes his name

p2.setLastName("Knopf");

System.out.println(p2);

}

}14.4. Solution - Create an Address object

The following is the expected result after the creation of an Address object.

package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

public class Address {

private String street;

private String number;

private String postalCode;

private String city;

private String country;

public String getStreet() {

return street;

}

public void setStreet(String street) {

this.street = street;

}

public String getNumber() {

return number;

}

public void setNumber(String number) {

this.number = number;

}

public String getPostalCode() {

return postalCode;

}

public void setPostalCode(String postalCode) {

this.postalCode = postalCode;

}

public String getCity() {

return city;

}

public void setCity(String city) {

this.city = city;

}

public String getCountry() {

return country;

}

public void setCountry(String country) {

this.country = country;

}

public String toString() {

return street + " " + number + " " + postalCode + " " + city + " "

+ country;

}

}package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

class Person {

String firstName;

String lastName;

int age;

private Address address;

public Person(String a, String b, int value) {

firstName = a;

lastName = b;

age=value;

}

public String getFirstName() {

return firstName;

}

public void setFirstName(String firstName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

}

public String getLastName() {

return lastName;

}

public void setLastName(String lastName) {

this.lastName = lastName;

}

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

public void setAge(int age) {

this.age = age;

}

public Address getAddress() {

return address;

}

public void setAddress(Address address) {

this.address = address;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

}package com.vogella.javastarter.exercises1;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// I create a person

Person pers = new Person("Jim", "Knopf", 31);

// set the age of the person to 32

pers.setAge(32);

// just for testing I write this to the console

System.out.println(pers);

/*

* actually System.out.println always calls toString, if you do not

* specify it so you could also have written System.out.println(pers);

*/

// create an address

Address address = new Address();

// set the values for the address

address.setCity("Heidelberg");

address.setCountry("Germany");

address.setNumber("104");

address.setPostalCode("69214");

address.setStreet("Musterstr.");

// assign the address to the person

pers.setAddress(address);

// dispose reference to address object

address = null;

// person is moving to the next house in the same street

pers.getAddress().setNumber("105");

}

}15. Type Conversion

If you use variables of different types Java requires for certain types an explicit conversion. The following gives examples for this conversion.

15.1. Conversion to String

Use the following to convert from other types to Strings

// Convert from int to String

String s1 = String.valueOf ( 10 ); // "10"

// Convert from double to String

String s2 = String.valueOf ( Math.PI ); // "3.141592653589793"

// Convert from boolean to String

String s3 = String.valueOf ( 1 < 2 ); // "true"

// Convert from date to String

String s4 = String.valueOf ( new Date() ); // "Tue Jun 03 14:40:38 CEST 2003"15.2. Conversion from String to Number

// Conversion from String to int

int i = Integer.parseInt(String);

// Conversion from String to float

float f = Float.parseFloat(String);

// Conversion from String to double

double d = Double.parseDouble(String); The conversion from string to number is independent from the local settings, e.g., it always uses the English notation for number. In this notation a correct number format is "8.20". The German number "8,20" would result in an error.

To convert from a German number, you have to use the NumberFormat class.

The challenge is that when the value is, for example, 98.00 then the NumberFormat class would create a Long that cannot be casted to Double.

Hence the following complex conversion class.

private Double convertStringToDouble(String s) {

Locale l = new Locale("de", "DE");

Locale.setDefault(l);

NumberFormat nf = NumberFormat.getInstance();

Double result = 0.0;

try {

if (Class.forName("java.lang.Long").isInstance(nf.parse(s))) {

result = Double.parseDouble(String.valueOf(nf.parse(s)));

} else {

result = (Double) nf.parse(new String(s));

}

} catch (ClassNotFoundException e1) {

e1.printStackTrace();

} catch (ParseException e1) {

e1.printStackTrace();

}

return result;

}15.3. Double to int

int i = (int) double;

15.4. SQL Date conversions

Use the following to convert a Date to a SQL date

package test;

import java.text.DateFormat;

import java.text.ParseException;

import java.text.SimpleDateFormat;

public class ConvertDateToSQLDate {

private void convertDateToSQL(){

SimpleDateFormat template =

new SimpleDateFormat("yyyy-MM-dd");

java.util.Date enddate =

new java.util.Date("10/31/99");

java.sql.Date sqlDate =

java.sql.Date.valueOf(

template.format(enddate));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

ConvertDateToSQLDate date = new ConvertDateToSQLDate();

date.convertDateToSQL();

}

}16. Java statements

The Java language defines certain statements with a predefined meaning. The following description lists some of them.

16.1. if-then and if-then-else

The

if-then

statement is a control flow statement. A block of code is only

executed when the test specified by the if part evaluates to

true.

The optional

else

block is executed when the

if

part evaluates to

false.

The following example code shows a class with two methods. The first

method demonstrates the usage of

if-then

and the second method demonstrates the usage of

if-then-else.

16.2. Switch

The switch statement can be used to handle several alternatives if they are based on the same constant value.

switch (expression) {

case constant1:

command;

break; // will prevent that the other cases or also executed

case constant2:

command;

break;

...

default:

}

// Example:

switch (cat.getLevel()) {

case 0:

return true;

case 1:

if (cat.getLevel() == 1) {

if (cat.getName().equalsIgnoreCase(req.getCategory())) {

return true;

}

}

case 2:

if (cat.getName().equalsIgnoreCase(req.getSubCategory())) {

return true;

}

}

// you can also use the same logic for different constants

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (int i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

switch (i) {

case 1:

case 5:

System.out.println("Hello");

break;

default:

System.out.println("Default");

break;

}

}

}

}16.3. Boolean Operations

Use == to compare two primitives or to see if two references

refer to the same object. Use the equals() method to see if

two different objects are equal.

&& and || are both Short Circuit Methods

which means that they

terminate once

the result of an evaluation is already clear.

Example (true || …)

is always true while (false

&& …) always is always interpreted as false. Usage:

(var !=null

&&

var.method1() …) ensures that var is not

null before doing

the real

check.

| Operations | Description |

|---|---|

|

Is equal, in case of objects the system checks if the reference variable point to the same object. It will not compare the content of the objects! |

|

And |

|

is not equal, similar to |

|

Checks if string a equals b. |

|

Checks if string a equals b while ignoring lower cases. |

|

Negotiation: return true if value is not true. |

17. Loops in Java

17.1. The for loop

A for loop is a repetition control structure that allows you to write a block of code which is executed a specific number of times. The syntax is the following.

for(initialization; expression; update_statement)

{

//block of code to run

}The following shows an example for a for loop.

public class ForTest {

public static void main(String args[]) {

for(int i = 1; i < 10; i = i+1) {

System.out.println("value of i : " + i );

}

}

}TIP:For arrays and collections there is also an enhanced for loop available. This loop is covered in the Array description.

17.2. The while loop

A while loop is a repetition control structure that allows you to write a block of code which is executed until a specific condition evaluates to false. The syntax is the following.

while(expression)

{

// block of code to run

}The following shows an example for a while loop.

public class WhileTest {

public static void main(String args[]) {

int x = 1;

while (x < 10) {

System.out.println("value of x : " + x);

x++;

}

}

}17.3. The do while loop

The do-while loop is similar to the while loop, with the exception that the condition is checked after the execution. The syntax is the following.

do

{

// block of code to run

} while(expression);The following shows an example for a do-while loop.

public class DoTest {

public static void main(String args[]) {

int x = 1;

do {

System.out.println("value of x : " + x);

x++;

} while (x < 10);

}

}18. Arrays

18.1. Arrays in Java

An array is a container object that holds a fixed number of values of a single type. An item in an array is called an element. Every element can be accessed via an index. The first element in an array is addressed via the 0 index, the second via 1, etc.

package com.vogella.javaintro.array;

public class TestMain {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// declares an array of integers

int[] array;

// allocates memory for 10 integers

array = new int[10];

// initialize values

array[0] = 10;

// initialize second element

array[1] = 20;

array[2] = 30;

array[3] = 40;

array[4] = 50;

array[5] = 60;

array[6] = 70;

array[7] = 80;

array[8] = 90;

array[9] = 100;

}

}18.2. Enhanced for loop for Arrays and Collections

Arrays and collections can be processed with a simpler for loop.

for(declaration : expression)

{

// body of code to be executed

}The following code demonstrates its usage.

package com.vogella.javaintro.array;

public class TestMain {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// declares an array of integers

int[] array;

// allocates memory for 10 integers

array = new int[10];

// initialize values

array[0] = 10;

// initialize second element

array[1] = 20;

array[2] = 30;

array[3] = 40;

array[4] = 50;

array[5] = 60;

array[6] = 70;

array[7] = 80;

array[8] = 90;

array[9] = 100;

int idx = 0;

for (int i : array) {

System.out.println("Element at index " + idx + " :" + i);

idx++;

}

}

}19. Strings

19.1. Strings in Java

The String class represents character strings.

All string literals, for example, "hello", are implemented as instances of this class.

An instance of this class is an object.

Strings are immutable, e.g., an assignment of a new value to a String object creates a new object.

To concatenate Strings use a StringBuilder.

StringBuilder sb =new StringBuilder("Hello ");

sb.append("Eclipse");

String s = sb.toString();Avoid using StringBuffer and prefer StringBuilder.

StringBuffer is synchronized and this is almost never useful, it is just slower.

19.2. String pool in Java

For memory efficiency Java uses a String pool.

The string pool allows string literals to be reused.

This is possible because strings in Java are immutable.

If the same string literal is used in several places in the Java code, only one copy of that string is created.

Whenever a String object is created and gets a string literal assigned the string pool is used.

For example, String s = "constant".

However, the new operator forces a new String copy to be allocated, for example, in String s = new String("constant");.

19.3. Compare Strings in Java

To compare the String objects s1 and s2, use the s1.equals(s2) method.

|

A This would work as expected. This comparison would fail. |

19.4. Working with Strings

The following lists the most common string operations.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

|

Return |

|

Return |

|

Define a new |

|

Return the character at position 1. (Note: strings are arrays of chars starting with 0) |

|

Removes the first characters. |

|

Gets the substring from the second to the fifth character. |

|

Look for the

|

|

Returns the index of the last occurrence of the

specified

|

|

Returns |

|

Returns |

|

Removes leading and trailing spaces. |

|

Replaces all occurrences of |

|

Concatenates |

|

Converts the string to lower- or uppercase |

|

Concatenate |

|

Splits the character separated |

20. Lambdas

20.1. What are lambdas?

The Java programming language supports lambdas as of Java 8. A lambda expression is a block of code with parameters. Lambdas allow you to specify a block of code which should be executed later. If a method expects a functional interface as parameter it is possible to pass in the lambda expression instead.

The type of a lambda expression in Java is a functional interface.

20.2. Purpose of lambda expressions

Using lambdas allows you to use a condensed syntax compared to other Java programming constructs.

For example, the Collection interface has a forEach method which accepts a lambda expression.

List<String> list = Arrays.asList("vogella.com","google.com","heise.de" )

list.forEach(s-> System.out.println(s));20.3. Using method references

You can use method references in a lambda expression.

Method reference define the method to be called via CalledFrom::method.

CalledFrom can be

* instance::instanceMethod

* SomeClass::staticMethod

* SomeClass::instanceMethod

List<String> list = new ArrayList<>();

list.add("vogella.com");

list.add("google.com");

list.add("heise.de");

list.forEach(System.out::println);20.4. Difference between a lambda expression and a closure

The Java programming language supports lambdas but not closures. A lambda is an anonymous function, e.g., it can be defined as parameter. Closures are code fragments or code blocks that can be used without being a method or a class. This means that a closure can access variables not defined in its parameter list and that it can also be assigned to a variable.

21. Streams

21.1. What are streams?

A stream from the java.util.stream package is a sequence of elements from a source that supports aggregate operations.

21.2. IntStream

Allows you to create a stream of sequence of primitive int-valued elements supporting sequential and parallel aggregate operations.

package com.vogella.java.streams;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.stream.IntStream;

public class IntStreamExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// printout the numbers from 1 to 100

IntStream.range(1, 101).forEach(s -> System.out.println(s));

// create a list of integers for 1 to 100

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<>();

IntStream.range(1, 101).forEach(it -> list.add(it));

System.out.println("Size " + list.size());

}

}21.3. Reduction operations with streams and lambdas

A reduction operation takes a sequence of input elements and combines them into a single summary result by repeating an operation.

package com.vogella.java.streams;

public class Task {

private String summary;

private int duration;

public Task(String summary, int duration) {

this.summary = summary;

this.duration = duration;

}

public String getSummary() {

return summary;

}

public void setSummary(String summary) {

this.summary = summary;

}

public int getDuration() {

return duration;

}

public void setDuration(int duration) {

this.duration = duration;

}

}package com.vogella.java.streams;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Random;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

import java.util.stream.IntStream;

public class StreamTester {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Random random = new Random();

// Generate a list of random task

List<Task> values = new ArrayList<>();

IntStream.range(1, 20).forEach(i -> values.add(new Task("Task" + random.nextInt(10), random.nextInt(10))));

// get a list of the distinct task summary field

List<String> resultList =

values.stream().filter(

t -> t.getDuration() > 5).map(

t -> t.getSummary()).distinct().collect(Collectors.toList());

System.out.println(resultList);

// get a concatenated string of Task with a duration longer than 5 hours

String collect =

values.stream().filter(

t -> t.getDuration() > 5).map(

t -> t.getSummary()).distinct().collect(Collectors.joining("-"));

System.out.println(collect);

}

}21.4. Example of filtering and mapping the content of a list

The following example demonstrates how to use streams to filter a list, perform a mapping operation and to create one final result string from it with the reduce method.

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class JavaStreamExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> list = Arrays.asList("Hello", "Streams", "Not");

String result = list.stream().

filter(s->s.contains("e")).

map(s-> s.toUpperCase() ).

reduce("", (a,b)-> a+ " " + b);

System.out.println(result + "!");

}

}21.5. Streams and lambda examples

The following is a larger example of the usage of streams. The code is based on the slides from the Goldmann Sachs Collection presentation at EclipseCOn 2015

Lets assume the following data model.

package com.vogella.java.streams;

public enum PetType {

DOG,

HAMSTER,

CAT,

BIRD

}package com.vogella.java.streams;

public class Pet {

private PetType type;

private String name;

private int age;

public Pet(PetType cat, String name, int age) {

this.type = cat;

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public PetType getType() {

return type;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

} package com.vogella.java.streams;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Collection;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Person {

public Person(String firstName, String lastName) {

this.lastName = lastName ;

this.firstName = firstName;

}

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

private List<Pet> pets = new ArrayList<>();

public Person addPet(PetType cat, String name, int age) {

pets.add(new Pet(cat,name, age ));

return this;

}

public boolean hasPet(PetType petType) {

return pets.stream().anyMatch(p-> p.getType().equals(petType));

}

public boolean isNamed(String string) {

return (firstName + " " + lastName).equals(string);

}

public List<Pet> getPets() {

return pets;

}

public Collection<PetType> getPetTypes() {

return pets.stream().map(pet-> pet.getType()).collect(Collectors.toSet());

}

public String getFirstName() {

return firstName;

}

public String getLastName() {

return lastName;

}

}With this data model you can use streams and lambdas to filter and search the data as demonstrated in the following example.

package com.vogella.java.streams;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.Collections;

import java.util.IntSummaryStatistics;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.Set;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class Example {

// examples based on

// https://www.eclipsecon.org/europe2015/sites/default/files/slides/2015-11-05%20EclipseCon-%20EclipseCollectionsByExample_0.pdf

private List<Person> people;

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<Person> persons = createData();

// do any of the persons have a cat?

boolean result = persons.stream().anyMatch(person -> person.hasPet(PetType.CAT));

// how many people have cats?

long catCount = persons.stream().filter(person -> person.hasPet(PetType.CAT)).count();

System.out.println(catCount);

// who has a cat?

List<Person> peopleWithCats = persons.stream().filter(person -> person.hasPet(PetType.CAT))

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// who does not have a cat

List<Person> peopleWithoutCats = persons.stream().filter(person -> !person.hasPet(PetType.CAT))

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// partition people with/without cats

Map<Boolean, List<Person>> catsAndNoCats = persons.stream()

.collect(Collectors.partitioningBy(person -> person.hasPet(PetType.CAT)));

// get the name of Tims cats

Person person = persons.stream().filter(each -> each.isNamed("Tim Taller")).findFirst().get();

boolean test = ("Dolly & Spot")

.equals(person.getPets().stream().map(Pet::getName).collect(Collectors.joining(" & ")));

System.out.println("Tim has Dolly & Spot as cats " + test);

// get the set of all pet types

Set<PetType> allPetTypes = persons.stream().flatMap(p -> p.getPetTypes().stream()).collect(Collectors.toSet());

System.out.println(allPetTypes);

// group people by their last name

Map<String, List<Person>> byLastName = persons.stream().collect(Collectors.groupingBy(Person::getLastName));

Map<String, List<Person>> byLastNameTargetBag = persons.stream()

.collect(Collectors.groupingBy(Person::getLastName));

System.out.println(byLastName);

// get the age statistics of pets

List<Integer> agesList = persons.stream().flatMap(p -> p.getPets().stream()).map(Pet::getAge)

.collect(Collectors.toList());

IntSummaryStatistics stats = agesList.stream().collect(Collectors.summarizingInt(i -> i));

System.out.println("Min " + stats.getMin() + " Max " + stats.getMax() + " Average " + stats.getAverage());

// counts by pet age

Map<Integer, Long> counts = Collections.unmodifiableMap(persons.stream().flatMap(p -> p.getPets().stream())

.collect(Collectors.groupingBy(Pet::getAge, Collectors.counting())));

}

private static List<Person> createData() {

return Arrays.asList(

new Person("Mary", "Smith").addPet(PetType.CAT, "Tabby", 2),

new Person("Tim", "Taller").addPet(PetType.CAT, "Dolly", 3).addPet(PetType.DOG, "Spot", 2),

new Person("Ted", "Smith").addPet(PetType.DOG, "Spike", 4),

new Person("Jake", "Snake").addPet(PetType.DOG, "Serpy", 1),

new Person("Lars", "Vogel").addPet(PetType.BIRD, "Twirly", 1),

new Person("Harry", "Hamster").addPet(PetType.HAMSTER, "Fuzzy", 1).addPet(PetType.HAMSTER, "Wuzzy", 1)

);

}

}22. Optional

If you call a method or access a field on an object which is not initialized (null) you receive a NullPointerException (NPE).

The java.util.Optional class can be used to avoid these NPEs.

java.util.Optional is a good tool to indicate that a return value may be absent, which can be seen directly in the method signature rather than just mentioning that null may be returned in the JavaDoc.

If you want to call a method on an Optional object and check some property you can use the filter method.

The filter method takes a predicate as an argument.

If a value is present in the Optional object and it matches the predicate, the filter method returns that value; otherwise, it returns an empty Optional object.

You can create an Optional in different ways:

// use this if the object is not null

opt = Optional.of(o);

// creates an empty Optional, if o is null

opt = Optional.ofNullable(o);

// create an empty Optional

opt = Optional.empty();The ifPresent method can be used to execute some code on an object if it is present.

Assume you have a

Task

object and want to call the

getId()

method on it. You can do this via the following code.

Todo todo = new Todo(-1);

Optional<Todo> optTodo = Optional.of(todo);

// get the ID of the todo or a default value

optTodo.ifPresent(t-> System.out.println(t.getId()));Via the

map

method you can transform the object if it is present and via the

filter

method you can filter for certain values.

Todo todo = new Todo(-1);

Optional<Todo> optTodo = Optional.of(todo);

// get the summary (trimmed) of todo if the ID is higher than 0

Optional<String> map = optTodo.filter(o -> o.getId() > 0).map(o -> o.getSummary().trim());

// same as above but print it out

optTodo.filter(o -> o.getId() > 0).map(o -> o.getSummary().trim()).ifPresent(System.out::println);To get the real value of an Optional the get() method can be used. But

in case the Optional is empty this will throw a

NoSuchElementException. To avoid this NoSuchElementException the

orElse

or the

orElseGet

can be used to provide a default in case of absence.

// using a String

String s = "Hello";

Optional<String> maybeS = Optional.of(s);

// get length of the String or -1 as default

int len = maybeS.map(String::length).orElse(-1);

// orElseGet allows to construct an object / value with a Supplier

int calStringlen = maybeS.map(String::length).orElseGet(()-> "Hello".length());23. System properties

The System class provides access to the configuration of the current working environment.

You can access them, via System.getProperty("property_name"), for example System.getProperty("path.separator");

The following lists describes the most important properties.

-

"line.separator" - Sequence used by operating system to separate lines in text files

-

"user.dir" - User working directory

-

"user.home" - User home directory

24. Schedule tasks

Java allows you to schedule tasks. A scheduled task can be performed once or several times.

java.util.Timer and java.util.TimerTask can be used to schedule tasks.

The object that implements TimeTask will then be performed by the Timer based on the given interval.

package schedule;

import java.util.TimerTask;

public class MyTask extends TimerTask {

private final String string;

private int count = 0;

public MyTask(String string) {

this.string = string;

}

@Override

public void run() {

count++;

System.out.println(string + " called " + count);

}

}package schedule;

import java.util.Timer;

public class ScheduleTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Timer timer = new Timer();

// wait 2 seconds (2000 milli-secs) and then start

timer.schedule(new MyTask("Task1"), 2000);

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

// wait 1 seconds and then again every 5 seconds

timer.schedule(new MyTask("Task " + i), 1000, 5000);

}

}

}TIP: Improved job scheduling is available via the open-source framework quartz. See https://www.onjava.com/lpt/a/4637 or https://www.quartz-scheduler.org/ for an explanation.

25. Links and Literature

Nothing listed.

25.1. vogella Java example code

If you need more assistance we offer Online Training and Onsite training as well as consulting